Milan San Remo has traditionally been known as the sprinter’s classic, due to its penchant for being the easiest classic to ride and consistently serving up fast-finishing winners. Despite being the longest race on the calendar at close to 300km, and featuring a mid-race mountain pass along with two climbs inside the final 20km, Milan San Remo has consistently been the lone chance for pure sprinters like Erik Zabel, Mark Cavendish, and Mario Cipollini to win a monument.

However, the last three years have seen a stark shift away from the pure sprinter demographic to more traditional allrounders and even GC contenders. Michał Kwiatkowski won from a breakaway group in 2017, Vincenzo Nibali took a spectacular solo victory in 2018, and Julian Alaphilippe won from a 12-person peloton in 2019. None of these winners would even remotely fit the role of a sprinter (Alaphilippe’s surprising bunch sprint victory at stage 6 of Tirreno-Adriatico aside).

With editions in the 2000s and 1990s dominated by true sprinters, we have to go all the way back to the late 1980s to find three consecutive victories for non-sprinters (Laurent Fignon ’88-’89 and Gianni Bugno ’90).

Part of the reason for this evolution is the increased speed the winners have been riding up the final climb of the race, the Poggio, which tops out 6km from the finish line.

On Saturday, the lead group of Julian Alaphilippe, Michal Kwiatkowski, Oliver Naesen, Alejandre Valverde, Peter Sagan, Matteo Trentin, and Wout Van Aert set the fastest time ever up the Poggio with a time of 5:37 (this is according to La Gazzetta Dello Sport. For the record, Kwiatkowski’s Strava file has him clocked at 5:41 with an average speed of 38.3km/h). This is over 30-seconds quicker than 2016, the last time a sprinter (Arnaud Démare) won the race, and more than a minute faster than 2014 when John Degenkolb took the victory.

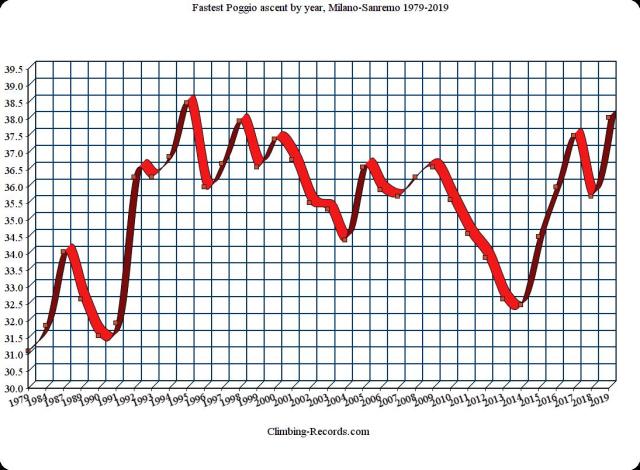

Below is a chart depicting the average speed for the fastest time up the Poggio from 1979-2019 courtesy of Mihai Cazacu at Climbing-Records.com (who recorded a slightly slower, but still second-best ever time of 5:50 and average speed of 38.06 km/h).

The chart depicts a noticeable increase in speed with the introduction of EPO to the peloton in 1991, along with a noticeable decrease with the introduction of the bio passport in 2009. Twitter anti-doping crusader Ufe recently published an annotated version of the chart.

While there can be endless debate about what the faster climbing times mean (for what its worth, level-headed cycling statistician Cillian Kelly seemed to find the increased speeds concerning shortly after the race) the fact is that the Poggio is being climbed with a ferocity we haven’t seen in years. It is difficult to imagine any pure sprinter staying with the lead group over the Poggio on Sunday following Deceuninck – Quick Step’s train, Alberto Bettiol’s race-splitting attack and Alaphilippe’s counter that killed off any sprinter’s chances.

The fact that Deceuninck – Quick Step possessed a huge pre-race sprint favorite in Elia Viviani and chose to completely spike that card by drilling it up the Poggio in an effort to flush out any sprinters and get Alaphilippe in a reduced group over the top shows the seismic shift the race has undergone in only three years. To see a team with likely the strongest sprinter specifically working to isolate an all-rounder in a group of normally faster finishers (Sagan, Trentin, Kwiatkowski, Matthews) was astonishing. The fact Alaphilippe won the race shows their supreme confidence was correct, but it was still bizarre to see a team purposely burn of their star sprinter in the “sprinter’s classic” (If I was Viviani, I would have been on the phone with my agent immediately following the race to see if any other teams need a sprinter).

There must be widespread headshaking amongst the biggest, faster riders in today’s peloton at the sight of their lone monument being overtaken by the allrounders and Grand Tour champions. But the lack of bunch finishes is likely welcomed by RCS.

The race organizer added the Poggio in 1960 after 89 riders made it to the line together in the 1959 edition. The climbed helped the attackers and reduced the size of the finishing group for a few years, but soon the sprinters began to dominate again.

To curb this domination, RCS added the Cipressa in 1982, but the increased speed of racing gave the sprinters the upper hand once again. RCS Sport planned to add an extra climb to the finale in 2014 an effort to burn off the fastmen and reduce the chances for big, boring sprint finishes.

While the plan to add an extra climb was thwarted by a landslide that rendered it unrideable, it seems the request for more aggressive racing has been answered organically. Whether by utilization of doping practices or simply realizing that riding up a climb faster makes it more difficult for riders that can’t ride up climbs as fast as you, Milan San Remo has seen a rapid evolution in the nature and speed of the finale.

This is all part of a larger trend of seeing the new wave of fast-finishing all-rounders that can climb with the best winning on all but the flattest, fastest finishes (which are featuring less and less in Grand Tours). It is hard to argue with the increased excitement factor, but it will be interesting to see if this new trend sticks, or if we see a reemergence or mass sprints on Via Roma once again.